The Amazon rainforest is suffering from forest fires, and the government of Brazil is scrambling to respond

Hi everyone, welcome back to Plain English, your recipe for English success. I’m Jeff, JR is the producer, and this is episode 185.

Coming up today: The Amazon rainforest is one of the world’s biological treasures, but it is suffering from more intense forest fires than usual. We’ll talk about what might be causing that, and what Brazil’s government is doing to respond. The phrase of the day is “up to the task,” and JR has a song of the week.

If you didn’t catch the previous special episode about Plain English Plus, I wanted to remind you about our new membership program that will help you take your English to the next level. To learn more about that, just visit PlainEnglish.com/plus.

Forest fires endanger Amazon rainforest

The Amazon rainforest is often described as the “lungs of the earth.” That’s because the 400 billion trees in the massive rainforest produce over 20 percent of the world’s oxygen. It is the largest rainforest in the world, and it represents half of the entire rainforest area on the planet. A rainforest is the most species-rich type of habitat there is: the Amazon itself is home to ten percent of all the species in the world.

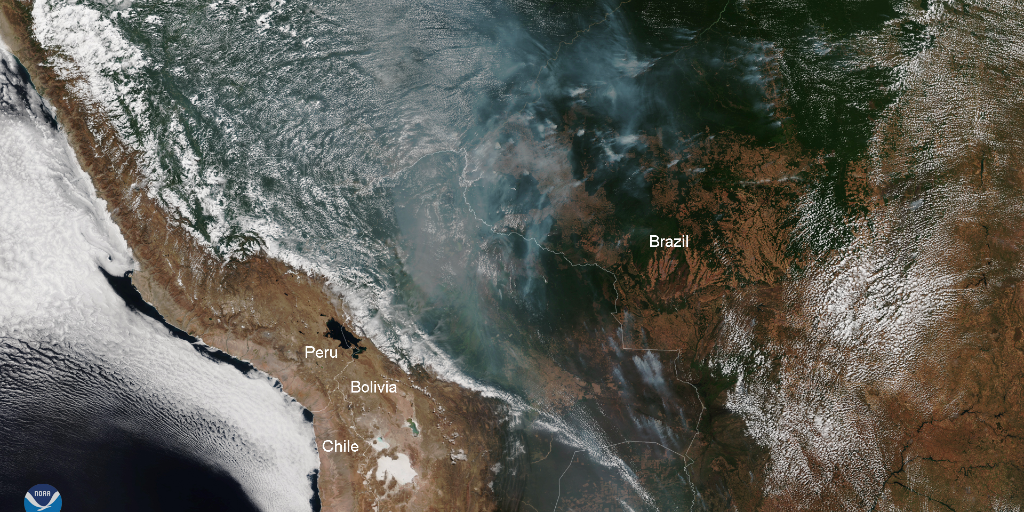

The Amazon is now burning at an alarming rate. Brazil’s National Institute for Space research has identified over 74,000 fires in the Amazon region this year. That is the most in a year since they began tracking Amazon fires in 2013.

Fires are a part of life and can even be healthy for forests, when they burn naturally. Some years have more intense forest fires than others. When there’s a drought, trees dry out. They shed leaves onto the forest floor and sometimes the trees themselves die. This provides the kindling for forest fires, which are often started by natural causes. Several factors typically keep Amazon forest fires under control. First, the general moisture and humidity in the region makes it hard for fires to spread. And second, the tree canopy—the greenery high above the ground—retains moisture down below and stops fires from getting too high. Most Amazon forest fires are minor and don’t reach more than a few inches or a foot off the ground. Long before people were ever on earth, fires have been a part of the cycle of life in the earth’s forest.

The problem comes when they are not natural. And there are two unnatural things that are making the fires worse this year. The first thing is when fires are started unnaturally; and the second thing is when the tree canopy is less protective than it should be.

Remember that the tree canopy is the highest part of the tree cover in a forest. It blocks sunlight, provides a habitat for many species, and retains moisture in the forest below. The tree canopy in many parts of the Amazon is damaged by deforestation and illegal logging. Deforestation is the process by which the forest is destroyed for agriculture, logging, mining, roads, dams, and things like that. That can have an effect on the tree canopy—and as a result, the forest provides less protection against fires down below.

The other cause is human activity nearby. People aren’t setting the fires simply to destroy; they are setting them for agricultural purposes. It’s common in farming to perform controlled burns to clear an area for cattle grazing or to replant crops. As humans clear more and more areas of the Amazon—frequently illegally—they bring their agricultural activities deeper and deeper into the Amazon region. And that is indeed what is happening: the fires are following the seasonality of agriculture and are in the areas neighboring the forest, not deep inside the forest far from human contact.

Preventing fires like this is a vexing challenge. Remember that the Amazon isn’t owned by anyone; there aren’t strong property rights, especially when land is being cleared illegally. As a result, there’s nobody there protecting the neighboring area, and no safeguard against setting fires recklessly. Think about this. If you and I are neighbors and we both have farms, you can bet that I’ll be keeping a close eye on you if you decide to do a controlled burn on your property. But what if there’s no neighbor? And what if the people setting the fires don’t own the land in the first place?

That is where the role of the government comes in—to prevent illegal logging and clearing and to enforce the laws against illegal burning, and to fight fires when they come up. Unfortunately, Brazil’s government hasn’t been up to the task. The rate of deforestation had slowed from the early 2000s until about 2012. Brazil strengthened its environmental protection agency, Ibama. The additional enforcement efforts, combined with an international Amazon Fund to help with conservation, were broadly working for about a decade. But then the deep recession hit Brazil and the funding for Ibama was cut. More recently, 21 out of 27 executives at Ibama have been fired and not yet replaced. The new president, Jair Bolsonaro, has taken a cavalier attitude in the past toward Amazon deforestation. Many think the federal government’s nonchalance about the issue has emboldened farmers, loggers, and miners in the Amazon region, who no longer fear enforcement of environmental laws.

The fires led to an international outcry. Brazilians protested in big cities, and foreign governments got into the mix. France’s president threatened to scrap a trade deal between Brazil and the EU over the crisis. In a bizarre combination of smoke from the forests and a unique weather pattern, darkness fell on São Paulo, Brazil’s largest city, at three o’clock in the afternoon one day. That only increased public pressure to respond to the crisis.

After spending a few weeks either denying or downplaying the crisis, Bolsonaro quickly changed tactics. He mobilized Brazil’s armed forces to fight the forest fires and enforce the environmental laws in the Amazon region. He said in a televised address that his government would have a “zero tolerance” approach to environmental crimes.

I want to say “hi” to a few listeners this week. First, Camila from Fortaleza, Brazil, is studying English to be a diplomat. And for the longest time, our web site, PlainEnglish.com, was not available in her area. Don’t ask me why. But Camila could not access the web site. And I tried and I investigated and I had no idea why she couldn’t get it—but then magically, she got it. The Internet Gods were nice to Camila and me, apparently. She now finally has access to the web site and the transcripts, which is such a relief. And thank you to Camila for repeatedly refreshing the page week after week. That’s persistence right there! Also I want to say hi to JP. He is studying English in Orlando, Florida. I asked how he likes the summers in Florida—they’re hot and humid—but he’s taking it in stride since he’s from Rio de Janeiro, a pretty hot city. JP says that listening to Plain English has made a huge difference in his listening abilities. I just love hearing that because I know how difficult it is to listen, especially when you’re in an English-speaking country. Not everyone goes as slow as we do here! If only, right? Thanks to Camila and JP for being loyal Plain English listeners.

Great stories make learning English fun