For the James Webb Space Telescope, it was a long journey to the launching pad

Lesson summary

Hi there everyone, it’s Jeff and this is Plain English, where we help you upgrade your English with current events and trending topics. JR is the producer and he has uploaded the lesson transcripts and all the other resources to PlainEnglish.com/493.

Four ninety-three, four ninety-three because we’ve got our five-hundredth lesson coming up. And we’re going to have a bit of a celebration for episode number five hundred. But it’s only going to be a success if you are involved. And the place you can get involved is PlainEnglish.com/500.

So when you’re done with today’s lesson, go to PlainEnglish.com/500 to be a part of the festivities.

Coming up today: it was years late and billions—and I mean billions—of dollars over budget. It was almost cancelled. The James Webb Space Telescope had a wild ride even before it took off. In the second half of the lesson, I’ll show you what it means to “have a crack at” something. Ready? Let’s dive in.

Webb’s long journey to launch

An Ariane rocket blasted off from the Kourou spaceport in French Guiana on Christmas morning 2021. That was the beginning of the James Webb Space Telescope’s million-mile journey into space. It was a moment that very nearly didn’t happen.

To understand, let’s look back in history a bit. The Hubble telescope launched in 1990. It was late and way over budget, but it proved to be invaluable for humanity’s understanding of the universe. It showed that all galaxies have a black hole at their center, that the universe’s expansion is accelerating, and it provided a close-up view of a comet crashing into Jupiter.

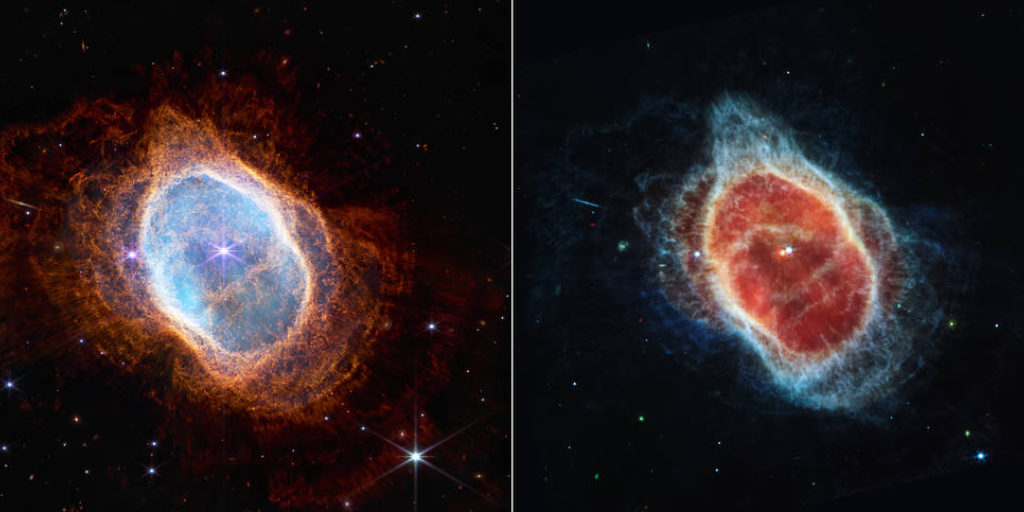

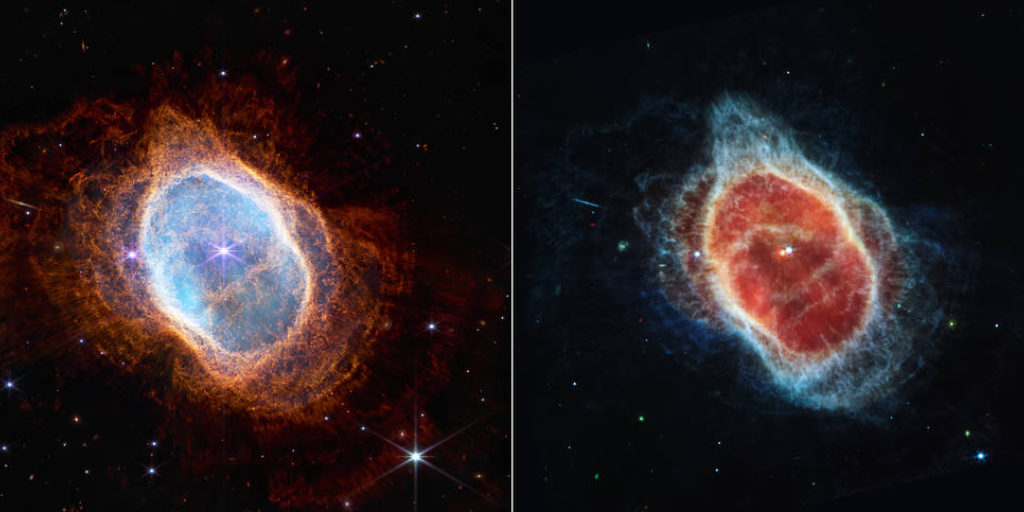

Just as the Hubble was at its height of success, NASA, America’s space agency, proposed a follow-up telescope, only this one would be bigger and would capture images in infrared light. Such a telescope—bigger, in a better location in space, and with infrared capabilities—this telescope would be able to build on the extraordinary findings of the Hubble.

Riding the scientific high of the Hubble, the U.S. Congress said “yes” to NASA’s proposal in 2002. The budget was $2.5 billion and it would launch in 2010. Fast-forward nine years, to 2011, and it was still not done. The new launch date was to be 2018, eight years late. Oh, and the budget was $8.8 billion, over three times the original budget.

That was a problem because the more money that went into the delayed telescope, the less money would be available for other space-related priorities. And, given how complex the project was, there was still no guarantee that it would ever work.

The U.S. House of Representatives gets the first crack at passing the spending bills that fund the government. And in 2011, the House cut $1.9 billion from NASA’s budget—the money intended for Webb. The Senate, the other half of our Congress, restored the funding before the final budget passed. But NASA was put on warning: Congress’s patience, and budget, was not unlimited.

Fast-forward again to 2018, the supposed launch date. The telescope wasn’t done; in fact , the project was in disarray. Over 10,000 people were working on it. The budget was now $10 billion, four times the original. And there was no end in sight. For every problem that was solved, another appeared. Conflict arose between NASA and the contractors building the telescope. People on the team weren’t communicating.

An editorial in the scientific journal “Nature” said: “No one should ever build a telescope in the way NASA built Webb.” Still, the prize was so valuable. So much had been invested. NASA had to do something.

NASA decided the project needed a new director. Gregory Robinson, a NASA veteran, transferred from another project to be the director of the Webb telescope. That proved to be a turning point . Slowly but surely, the project started to hit its milestones. Robinson’s supervisor at NASA called him “the most effective leader of a mission I have ever seen.” And as we all know, the telescope launched successfully in late 2021.

The big test, though, was not in the launch, but in the first few weeks of the mission. The telescope had over three hundred “single-point failures.” That means that if any one of those three hundred things had gone wrong, the whole telescope would have been doomed. But none went wrong. The telescope launched successfully. It then performed some acrobatics: it had to unfold and assemble itself in space, since it was too bulky to lift off in its final state.

All that worked and, as you heard last week, the first images came back to Earth. Still, there was a little initial damage. The telescope’s mirror has 18 gold-plated segments. One segment was damaged by a micrometeoroid. That’s a fragment of a meteor that could be as small as a grain of sand. Micrometeoroids were expected, but this damage came early. NASA said it can’t repair the mirror, but it can make adjustments to partially correct for the damage.

A few more details

Here are a couple of interesting things I discovered when researching these two lessons. First, any astronomer—any person in the world—can use the telescope, if their application is accepted. So astronomers apply to the Space Telescope Science Institute. And the institute reviews all applications without knowing who’s applying. They decide who gets time on the telescope based on how valuable their inquiry is, on the merits of the proposal only, not the reputation of the astronomer, not the prestige of the university, not the country, nothing. The decisions are made without knowing who the applicant is. And I saw in one article that an astronomy student got approval to use the telescope, which is cool.

The other thing I found out is what scientists get when they get “time on the telescope.” So the telescope can work—not 24/7, but for a certain number of hours in the year. So the scientists who apply, and who are approved, get “time on the telescope.” But I didn’t know what that exactly meant.

So I asked the question on Quora; I’ll put the link to the question in the transcript.

A few astronomers replied and here’s what they said. With a complicated telescope, the astronomer tells the agency what to observe. And obviously this part is far more complicated than I’ll ever understand, but basically the astronomers’ proposal says what they want to see, what sensors need to be used, what data needs to be gathered. And the operators of the telescope point the mirrors and configure the telescope to get the images and the data that the astronomers want. And they arrange the projects such that projects with similar specifications are done together.

And then the astronomers can download the data at a particular point and analyze it afterward, without ever going anywhere, without ever leaving their lab or office.

Learn English the way it’s really spoken