There’s a new book by Gabriel García Márquez, the famous Colombian writer. The publisher describes it as “more irrefutable proof of his talent, dedication, and love for literature.” His fans love the story. But one critic disagreed. This critic said the book doesn’t work; he even went so far as to say the book should be destroyed. That critic is García Márquez himself. His wish, before he died ten years ago, was that this book should never be published. But now his sons have published it anyway, and have asked for their father’s forgiveness.

Lesson summary

Hi there everyone, I’m Jeff and this is Plain English, where we help you upgrade your English with stories about current events and trending topics.

You heard today’s story: “Until August,” the new novella by the Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, was published against the writer’s wishes. Should his family have published this book or not?

In the second half of the lesson, I’ll show you a difficult English expression: “cloud your judgment.”

Now before we get started, just a note on vocabulary. In English, a novel is a fictional story that, in print, is usually anywhere from 200 pages to much more, but usually 300, 400 pages, something like that. A novel is something you read over many hours, in several sittings. There’s a lot of time for the author to develop the story.

A short story is much slimmer. In print, it’s anywhere from 5, 10 pages to, say, 30 or 40 pages. But you read it in one sitting.

A novella is something that fits in between. It’s longer than a short story. You would spend a few hours with it. But it’s not as long, it’s not as fully developed, as a novel.

The difference is not just about page count—a novel and a short story are really two different art forms. But just to make things simple: a novel is long, a short story is short, a novella is somewhere in the middle. And “Until August,” in print, is only about 100 pages, so I’m going to call it a novella in this story.

All right, get ready. This is another episode where you’re going to have to make a tough judgment. So let’s get going.

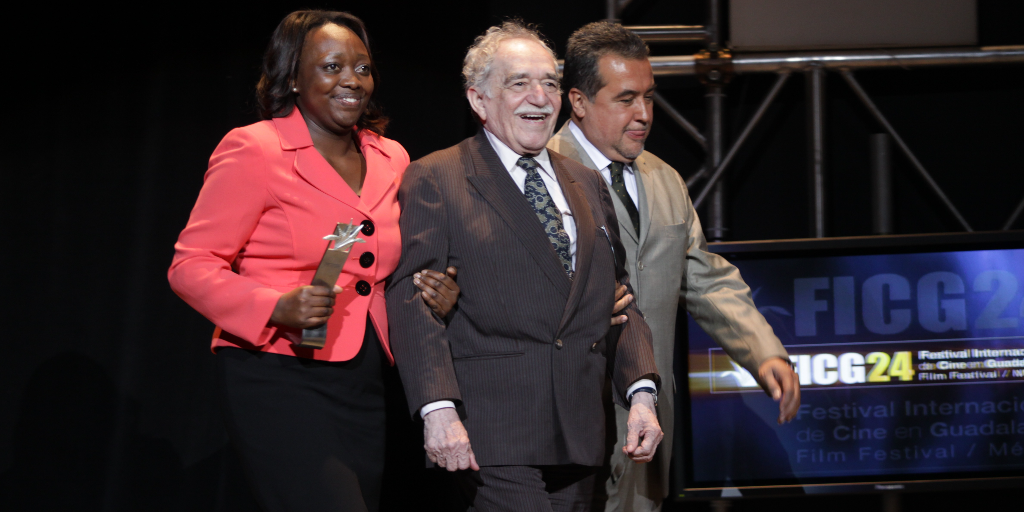

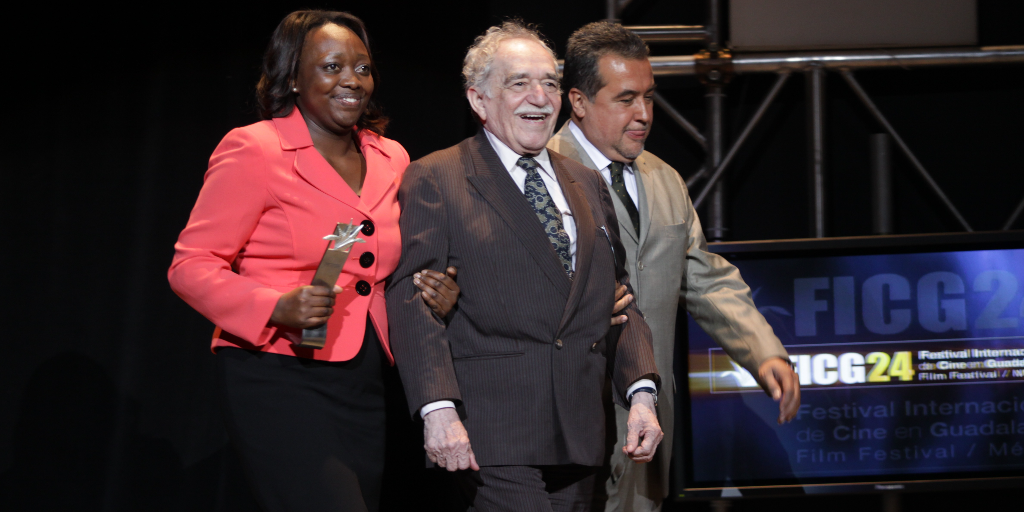

Gabriel García Márquez’s novel was published against his wishes

Gabriel García Márquez was a Colombian writer. He wrote novels, short stories, non-fiction works and screenplays over a forty-year career. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982, becoming the first Colombian, and only the fourth Latin American writer, to win the prize.

The Nobel committee cited his “his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent’s life and conflicts.”

Though he spent much of his life outside Colombia, García Márquez often wrote about the region he grew up in: Colombia’s Caribbean coast. That’s the setting of two of his most famous works: “One Hundred Years of Solitude” and “Love in the Time of Cholera.”

It’s also the setting of “Until August,” a novella that García Márquez worked on intermittently for decades. It tells of Ana, who makes an annual trip to visit her mother’s grave every August. She takes a ferry to an offshore island, stays one night in a run-down hotel, and returns home.

One year, she meets a stranger at a hotel bar and they have a one-night sexual encounter. In subsequent years, she makes this part of her annual pilgrimage: she meets a new man each time.

García Márquez conceived “Until August” as just one of four stories in a larger collection. Though he started the book in the late 1990s, he set it aside to work on other projects. He picked it up again in the mid-2000s, but still didn’t finish it. He said he was happy with the protagonist, but he wasn’t happy with the plot.

He was never able to finish it to his satisfaction. As he aged, García Márquez slipped into dementia and was unable to finish the novel or the other stories—”Until August” was the only story of the collection that he drafted. And in those final, cloudy years, he gave his verdict: “This book doesn’t work,” he said. “It must be destroyed.”

García Márquez died in April 2014. He left five drafts of this manuscript. They were never published, but they were placed in his archive in Texas, where scholars could visit and study them. But now, on the tenth anniversary of the writer’s death, his two sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo, have decided to publish the novella against their father’s wishes.

Were they right to do so?

Here is what the sons said in the preface of “Until August.” They asked, “was it a betrayal to our father’s wishes?” And they concluded that yes, it was a betrayal. But, they said, “that’s what children are for.”

They argue that the story is far better than their father believed it to be. García Márquez was unable to finish the novella, owing to his memory loss. But that same memory loss might have clouded his judgment . He might have been unable to see how good the work really was.

As he was suffering from dementia, he confided in his family that he felt lost as an artist and he often didn’t even recognize his own work. That was his state of mind when he proclaimed “Until August” to be unworthy.

Here’s yet another complication: García Márquez did like the story earlier in life. He published parts of it in magazines and even read from it during a lecture at Georgetown University. So if he liked it enough to publish parts of it, and if he liked it enough to read from it in public, and if he only condemned it when he was already suffering from dementia, then should it really be hidden forever?

García Márquez’s sons also argue that the work belongs to readers, that it belongs to the body of literature, and that it would be a greater betrayal to deprive the world of this work. “We decided to put his readers’ pleasure above all other concerns,” his sons write. “If they are delighted,” they say, “it’s possible [he] might forgive us.”

In a later interview, they said that there are plenty of examples of manuscripts, which writers wanted to destroy, but which later became important works of literature.

There’s another argument for releasing “Until August.” This was García Márquez’s only unpublished work, so by releasing it, his sons have given the world a complete collection from the famous writer. There’s nothing else lurking in a box somewhere, no other scraps of unfinished works, nothing coming out in another ten years. This is it: the world now has the full literary work of Gabriel García Márquez to study, to enjoy, to learn from, to be inspired by, now and forever in the future.

But there are good arguments against posthumously publishing an unfinished work. First, this does go against the writer’s specific wishes. It would be a clearer case if the story were almost complete, and if the writer had died before he could finish editing it. But that isn’t what happened here. In this case, the novella was complete—or as complete as García Márquez was going to make it. And yet he still said it should be destroyed.

What’s more , an artist’s legacy is as much about what was released as about what was not released. We, in the public, don’t have the right to all the other drafts, to the rejected pages, the crossed-out lines, the ideas that went nowhere. That goes for paintings, music, photography, literature—every form of art. So why should we have the right to a mostly-finished story, just because some people—not the artist—some people thought this rejected draft was good enough to bear the artist’s name?

Next, the text that was released is not the final text that García Márquez wrote—for the simple fact that there were five drafts in various states of completion, plus fragments and notes spread over more than 700 pages. García Márquez marked one manuscript as “OK.”

The writer’s editor, Cristóbal Pera, said that, as he compiled the final version, he stayed true to the manuscript and fragments that García Márquez preferred. He did not add any words that García Márquez did not write. Pera, the editor, only compiled the parts that had already been written. He said he worked like a “restorer facing a great master’s canvas.” Even so, careful readers will wonder how much license the editor took when assembling the final draft.

Finally, some fans will get an uneasy feeling that the book was published less for the writer’s legacy than for his family’s desire to squeeze a little more out of the writer’s estate on the anniversary of his death.

Jeff’s take

This is a tough one. I agree with the Colombian journalist Juan Mosquera who said, “They’re not offering it to you as a manuscript, as an unfinished work, they are offering you the last novel by García Márquez,” which this really isn’t.

Here is what I would have decided. Respect the writer’s wishes as much as possible, without depriving the world of something. And for that I would say, the five drafts should have been available, intact, the way he left them, without an editor’s interference, and they should have been made available with his papers at his archives.

That way, scholars and super fans could have read it and studied it, in context, all five drafts, maybe even online, as a historical artifact. But to publish it commercially, to put the author’s name on it, to say it’s his final book, to design a cover, to put it on bookshelves, to sell it, I think, crosses a line .

Learn English the way it’s really spoken